Supreme Court Patent Decision -- Can Thinking Infringe a Patent?

Wow! The upcoming Supreme Court case in Laboratory Corporation of America Holdings v. Metabolite Laboratories, Inc. ought to be an interesting one, even if you are not a patent lawyer. The decision below from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (LabCorp v. Metabolite, 370 F3d 1354 (Fed. Cir. 2004) affirms the District Court jury decision that LabCorp indirectly infringed Metabolite's patent and holds that it directly infringed the patent as well.

Here is the story: Researchers developed a test that showed that high levels of homocysteine (an amino acid in the body) were indicative of vitamin deficiencies. They applied for, and received, a patent on their test, which was an improvement on previous tests. The researchers however, claimed a patent in the physiological fact itself, since they were the first to recognize the correlation. This was actually granted, and is known as the '658 Patent (short for U.S. Patent No. 4,940,658).

The researchers licensed their patents to Metabolite, who then licensed them to LabCorp. LabCorp was properly paying royalties everytime it used the patented test method. But then Abbott Laboratories developed a new homocysteine test that LabCorp thought was better, and was different enough that it did not infringe the patent. LabCorp began to use the Abbott test instead. No infringement.

But then LabCorp published an article stating that high homocysteine levels might indicate a vitamin deficiency. Metabolite sued -- patent infringement -- $5 million damages!

The U.S. Court of Appeals in the Federal District -- the court that handles all patent appeals -- heard LabCorp's appeal. And affirmed. And said that not only did LabCorp infringe the '658 Patent by publishing the article, but finds that LabCorp solicited physicians to infringe the patent by publishing continuing education material stating the physiological fact that high homocysteine levels correlate to vitamin deficiencies which can be treated with vitamins:

The record contains such evidence of intent. LabCorp’s own publications supply much of this evidence. LabCorp publishes both Continuing Medical Education articles as well as a Directory of Services that are specifically targeted to the medical doctors ordering the LabCorp assays. These publications state that elevated total homocysteine correlates to cobalamin/folate deficiency and that this deficiency can be treated with vitamin supplements. LabCorp’s articles thus promote total homocysteine assays for detecting cobalamin/folate deficiency.

Faced with these statements, LabCorp attempts to explain that these articles focus on heart disease rather than vitamin deficiency. As noted earlier, the patent does not require a correlation to some particular medical condition, but to a vitamin deficiency. The publications advocate use of the assay to identify a need for cobalamin/folate supplements. Thus, the vitamin deficiency remains the focus of the assay and the treatment (i.e., vitamin supplements).

Accordingly, a reasonable jury could find intent to induce infringement because LabCorp’s articles state that elevated total homocysteine correlates to cobalamin/folate deficiency. Moreover, the publications recommend treatment of this deficiency with vitamin supplements. Because “[i]ntent is a factual determination particularly within the province of the trier of fact,” Allen Organ Co. v. Kimball Int’l, Inc., 839 F.2d 1556, 1557 (Fed. Cir. 1988), this court sees no reason to disturb the jury’s finding regarding LabCorp’s intent. Therefore, this court affirms the finding of indirect infringement based on the inducement analysis. This court declines to consider contributory infringement.

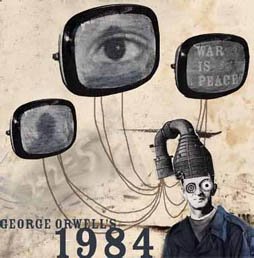

It will be interesting to watch what the Supremes make of this holding. It looks to me like patent law is spilling over into thought control.

No comments:

Post a Comment