Cool is defined in "Da Bomb's Mini-dicitionary of Slang" here:

cool: (adjective) 1. Calm. 2. Fine, acceptable. 3. Neat; exciting; interesting; very good.

It goes beyond these things to define the desirable state of being considered part of an attractively insider group. The most cool define their own group, rather than following some other party's dictates of fashion.

Slang can often be a large part designating coolness, and subtly (or not so subtly) designating those outside the inner group. See the online page of current college slang here. This is also the site with Da Bomb's Mini-dictionary. One of the aspects of coolness they note in slang is a playfulness, a sense of fun with the language. The slang not only defines the inner group and excludes non-belongers, it also becomes a kind of performance art. It exhibits how current the slanger is. But you would never speak slang to a dean or parent the way you would to a close friend. Slang makes reference to closely shared experiences, and helps reinforce your friendships, while being fun, humorous, and even rising to the level of art.

Cool has long been identified with rebellion against parents and the powers that be. Jazz, rock and roll, blue jeans, even long ago, rag-time were all considered somehow linked with sex, drugs and undermining authority. And that is cool, somehow. From the 1920's decadence, cool took a definite break during the Great Depression. Then it broke out again with the development of Swing Jazz and Dance during the 1940's. The Beat Generation was cool with coffee, cigarettes and poetry. And Elvis Presley wiggling his pelvis in television -- mass hysteria and a new definition of cool. Then rock and roll in the '60's - blue jeans and Woodstock: another kind of cool.

Here is an interesting book that looks at how corporate advertising has hijacked the popular images of cool for selling products. The Conquest of Cool Business Culture, Counterculture, and the Rise of Hip Consumerism by Thomas Frank. See a generous excerpt here.

rebel youth culture remains the cultural mode of the corporate moment, used to promote not only specific products but the general idea of life in the cyber-revolution. Commercial fantasies of rebellion, liberation, and outright "revolution" against the stultifying demands of mass society are commonplace almost to the point of invisibility in advertising, movies, and television programming. For some, Ken Kesey's parti-colored bus may be a hideous reminder of national unraveling, but for Coca-Cola it seemed a perfect promotional instrument for its "Fruitopia" line, and the company has proceeded to send replicas of the bus around the country to generate interest in the counterculturally themed beverage. Nike shoes are sold to the accompaniment of words delivered by William S. Burroughs and songs by The Beatles, Iggy Pop, and Gil Scott Heron ("the revolution will not be televised"); peace symbols decorate a line of cigarettes manufactured by R. J. Reynolds and the walls and windows of Starbucks coffee shops nationwide; the products of Apple, IBM, and Microsoft are touted as devices of liberation; and advertising across the product category sprectrum calls upon consumers to break rules and find themselves.

Frank's excerpt includes some thought-provoking images of advertisements that use "cool" to sell products such as car models. Frank's actual premise is that right from the beginning, corporations were following, co-opting and using the counter-culture. He produces many examples to show that the advertisers and corporate world did not wait to absorb and re-fashion cool for their own purposes.

One more book examination of Cool, The Laws of Cool: Knowledge Work and the Culture of Information, by Alan Liu, reviewed here.

Here is an excerpt from Susan Shreiber's interesting review of the book:

... one of Liu's final chapters entitled "Historicizing Cool: Humanities in the Information Age," in which he ponders the role of education as a parallel anti-universe of cool. Liu argues that anti-learning, or learning that does not happen within the education system, is a turning away from "an education system it believes represents dominant knowledge culture toward a popular culture whose corporate and media conglomerates, ironically, are dominant knowledge culture." (p. 305) Although Liu writes that the cool themselves realize the irony of their own positions, he also demonstrates how humanities education has failed to demonstrate that cool itself is a historical condition and lacks understanding of how cool is of and not outside history. This recognition would go a long way in countering the routine charge by postindustrial business that humanities education is obsolete, inefficient, and irrelevant. Indeed, in reading, or more specifically, in re-reading, The Laws of Cool, one realizes that countering this charge is the central premise of the text.

Shreiber, p. 112.

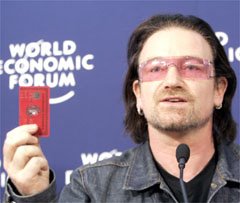

The picture decorating this essay is of U-2 Irish musician Bono. He and Bobby Shriver, Chairman of DATA (Debt, AIDS, Trade Africa), created RED to engage the private sector in the fight against AIDS in Africa. They included corporate partners such as American Express, Converse, Gap and Giorgio Armani. On January 26, 2006, at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, Bono and Bobby Shriver announced Product RED, an economic initiative designed to deliver a sustainable flow of private sector money to the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. It is the first time that the world’s leading companies have made a commitment to channel a portion of profits from sales of specially–designed products to the Global Fund to support AIDS programmes in Africa with a focus on women and children.

Now, that's defining your own standard of cool.

No comments:

Post a Comment