Know Thyself: Students, Self Assessment, Skills Training

In the May 5, 2006 Chronicle of Higher Education insert, The Chronicle Review, an essay, "Not Knowing Thyself" appears on page B24. By Professor David Dunning, a psychologist at Cornell University, the essay bewails the inability of students of all types to accurately assess themselves. Prof. Dunning asserts that students consistently over-rate themselves in studies. This is a very distressing essay.

We actually have heard this before, from Joan Shear at Boston College, for instance. Prof. Dunning cites studies by Donald A. Risucci and colleagues at North Shore University Hospital in Manhasset, NY, where residents on surgical rotation were asked to rate their clinical competence just before taking the standard in-training exam administered by the American Board of Surgery. Supervisors and peers predicted very well how residents would perform. However, the residents rated themselves much more competent then they were.

Another study of medical students, interns at the University of Sydney, studied by Les Barnsley, asked the interns if they were competent in performing common medical procedures. 100% of the interns felt they were competent enough to do without further supervision inserting a catheter into a male bladder (ouch!), while only 50% of supervisors grading their performance agreed. Nobody apparently asked the patients' opinions. When researchers asked the interns if they were competent enough to teach others the procedure, 80% felt they were ready. None of the supervisors agreed.

Prof. Dunning says, eloquently, heartbreakingly, and depressingly:

Take as one example work we have done in my laboratory on the plight of the incompetent. In many intellectual and social domains, such people suffer a double curse. First, because they lack knowledge and skill, they make many mistakes. and second, because of these same deficits, they cannot recognize the inferiority of their decisions and the superiority of the decisions made by others -- so they do not even realize that they should seek advice before acting.

Evidence points out just how unaware incompetent people are of their shortcomings. When we give students tests of logic, grammar, and interpreting others' body language, those performing at the bottom usually think they are doing better than a majority of their peers.

This is pretty close to what I recall Joan Shear talking about a few years ago. So what can we do to help students understand what they don't know? How can we help them become better assessors of themselves as legal researchers or as law students, or as young lawyers?

Prof. Dunning has some comments that I thought were helpful. He suggests that some common educational practices simply promote overconfidence, and lead to failure in the real world. For instance, he suggests that drilling students in one or a few intense training periods is a back-firing method. Students learn quickly, and at the end of the training, they appear to be competent.

Unfortunately, the quick acquisition does little to promote retention of a skill, according to Prof. Dunning. This certainly fits with my own experience. If I don't keep practicing a quickly learned skill, that skill begins to atrophy. Then, in the future, when a situation comes up and I need that skill, if I think I know it, because I drilled and tested successfully, and the skill is not really there, I am much more likely to fail. This might be why so many new drivers have accidents. They drill and drill on skill sets, learn things quickly, but have not had time to truly absorb the skills. They drive off confidently. When the car skids, they don't really remember to turn the wheel with the skid. OOOPS!

So, instead of drill, drill, drill, what would Prof. Dunning suggest instead? He refers the reader to Professor Robert A. Bjork, psychologist at U.C.L.A. who suggests "distributed training." This amounts to a series of short training sessions, spaced over a longer period of time. The article also suggests introducing real-world difficulties into the training sessions, less feedback from instructors and varying the schedules of training. I suppose all those things make the training more like the real world. It also makes it more difficult and irritating for the students, so we should be ready for lower student evaluations. Such training also leads students to be less confident in their own skill levels. But Prof. Dunning also asserts that it also leads to greater retention of the skills when it is time to apply them in the real world.

Three more suggestions from Prof. Dunning:

1) Let the students test themselves frequently. They can take quizzes, estimate how well they think they did on the quiz, and then compare that to how well they really did on the quiz. Teach them to be alert to weaknesses in their expertise and understanding and to use the results to relearn what they missed, as well as to congratulate themselves on knowledge they have gained.

2) Let the students compare themselves against each other's approach to the same problem. This is the "Grand Rounds" method. Show or discuss one or more student's solution to a problem and make sure the students are alert to consider how they did. Besides comparing themselves, it will offer many new solutions to the problem.

3) Peer Feedback; apparently peers do just about as good a job evaluating each other as the teacher does. According to Prof. Dunning, studies show that students earn higher marks when peers evlauate their work.

Finally, here is one last comment about the importance of knowing thyself. This essay is from the National Journal, May 8, 2006 edition, link here. William Chamberlain, Assistant Dean, Law Career Strategy and Advancement, Northwestern University School of Law. Mr. Chamberlain, essay, "KNOW YOURSELF The Benefits of Self-Assessment" speaks of the importance of knowing what type of person you are when thinking about the type of law practice that would suit you. He speaks of different personality indicators, such as Myers-Briggs, and refers the reader to books such as What Color is Your Parachute. These are good things to think about. When one considers the rate of unhappiness among new lawyers, they are very good things to think about.

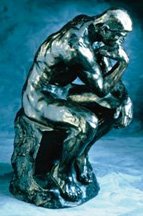

The decoration is Rodin's sculpture The Thinker, image courtesy of The University of KY, art museum, www.uky.edu/ (my alma mater).

1 comment:

Thanks for this discussion :)

Post a Comment